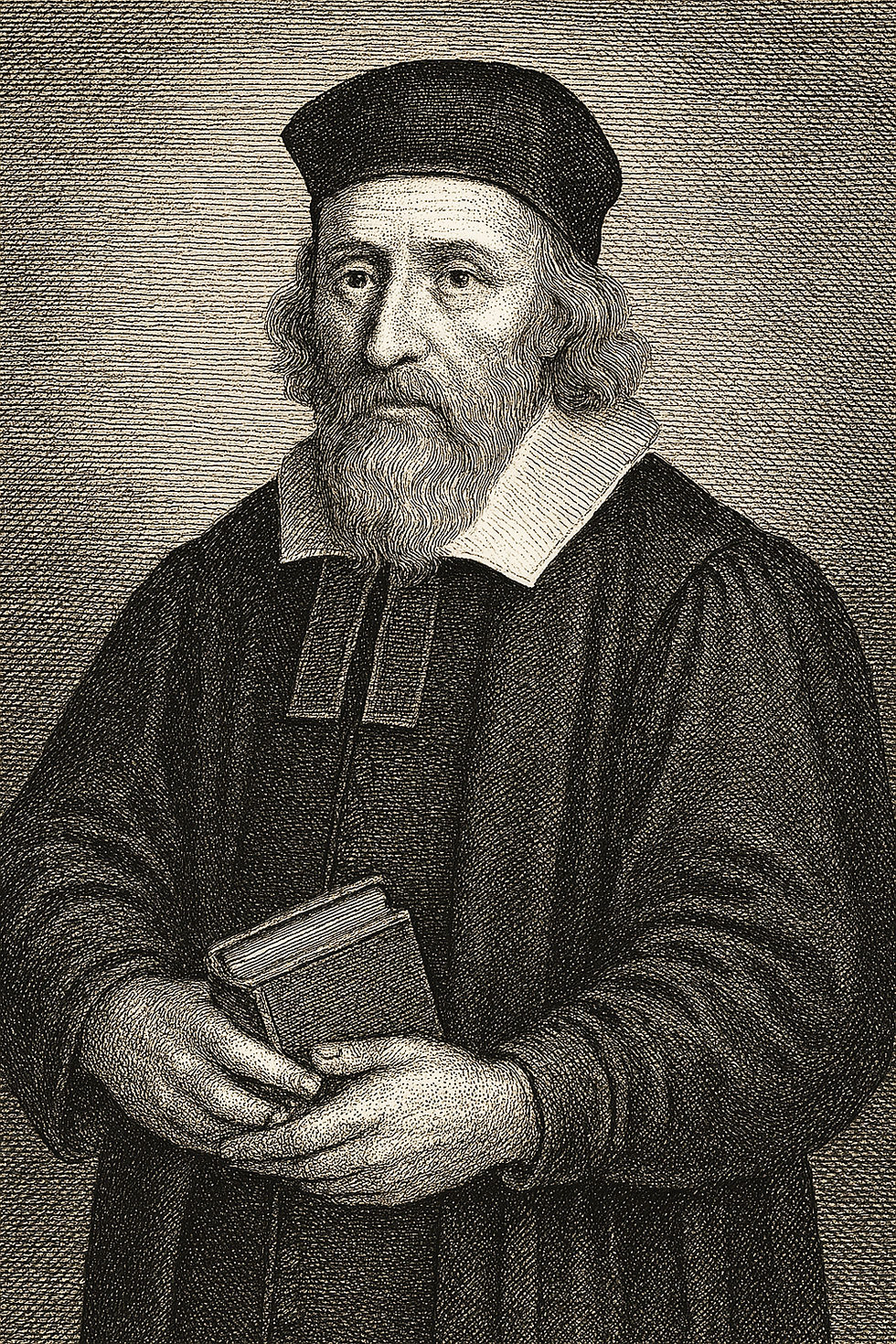

Rev. John Forbes of Alford: A Voice of Conscience in Turbulent Times

- Bart Forbes

- Jul 22, 2025

- 8 min read

Updated: Jan 12

John Forbes of Alford was a Scottish theologian and clergyman whose life spanned one of the most turbulent periods in the religious and political history of Scotland. A staunch Presbyterian and a man of principled conviction, Forbes is remembered for his unwavering dedication to the Reformed faith, his role in ecclesiastical conflicts with the monarchy, and the legacy he left through his writings.

John Forbes was born around 1568 to William Forbes, 4th laird of Corse, and his wife, Elizabeth, who was the daughter of John Strachan of Thornton. He was the younger brother of Patrick Forbes, who would become 5th laird of Corse, Bishop of Aberdeen, and Chancellor of King’s College of the University of Aberdeen. Bishop Forbes had a son also named John (1593–1648), who would become a distinguished theologian in his own right and followed in his father’s footsteps by becoming a professor at King's College in Aberdeen. (Tayler, Alistair and Henrietta. 1937. House of Forbes. Edinburgh: Third Spalding Club.)

John Forbes of Alford studied at the University of St Andrews, where he trained in theology and philosophy for about eight years. He studied under Andrew Melville (1545-1622) whose teachings were more radical than those of John Calvin (1509-1564) and the Scottish Reformer, John Knox (c. 1515-1572). Knox had fueled the Scottish Reformation and founded the Church of Scotland in 1560. The new Church adopted a Presbyterian structure and primarily Calvinist doctrine.

Forbes was greatly influenced by Melville, who believed in a more thorough reformation of the church that rejected “all ecclesiastical institutions, ritual and ceremonies that were not explicitly sanctioned by the Scriptures.” (de Jong, Chris. 1989. “John Forbes, Scottish Minister and Exile in the Netherlands,” Nederlands archief voor kerkgeschiedenis / Dutch Review of Church History. Leiden: De Gruyter Brill.) He also believed that the Presbyterian church should be strongly defended against infringement by the state. This “formed the intellectual climate in which Forbes's theology was shaped.” (Ibid.)

After completing his studies, Forbes entered the ministry and was ordained in the Church of Scotland. He was appointed minister of Alford in Aberdeenshire in 1593. His intellectual depth, pastoral care, and firm adherence to Presbyterianism quickly gained him a reputation as a respected churchman and scholar. Based on his studies under Melville, he believed in the authority of presbyteries and the independence of the church from civil authorities in spiritual matters. He rejected episcopacy (the rule of bishops) and royal interference in church governance, a position that would bring him into direct conflict with the monarchy.

Forbes's first confrontation with authority occurred during the reign of King James VI of Scotland over the excommunication of George Gordon, 1st Marquess of Huntly. Huntly had been a staunch Catholic for decades. However, the King demanded that he should renounce (abjure) “Romanism” (the Roman Catholic Church) or be banished. He submitted to the Kirk in June 1597. However, the Synods of Aberdeen and Moray found reason to doubt his abjuration and excommunicated him. Huntly had appealed to the Privy Council, which overturned the excommunication.

The Synods of Aberdeen and Moray recruited Forbes to defend the excommunication directly before the King. In their letter to James, the leaders of the Synod stated that Forbes had been chosen for this role because of “his fidelity and uprightness, and his sincere affection borne to the kingdom of God, his majesty’s service and peace of the land.” (Stephen, Leslie, and Lee, Sidney, Editors. 1908. Dictionary of National Biography, Volume VII. New York: MacMillan Company.) He was received by the King in March 1605 and proved his case.

However, later that year, Forbes presided over the General Assembly, which determined doctrine for the Church of Scotland. This meeting had not been authorized by the King and was considered illegal. Refusing to disband at the King's order, Forbes and several others were arrested and charged with treasonous disobedience. Though initially imprisoned, they were eventually tried and banished. In November 1606, he and the other ministers left for France. (McMahon, C. Matthew, Editor. 1635, Reprinted 2018. “Preface,” The Christian’s Charge: Never to Offend God in Worship. Crossville, Tennessee: Puritan Publications.)

In 1608, John Forbes traveled to Sweden at the request of King Karl IX. The Protestant Church of Sweden was heavily influenced by the teachings of Martin Luther whereas the doctrines of the Church of Scotland were shaped by the principles of John Calvin and John Knox. The King was interested in revising some of the Lutheran doctrines. At the King’s request, Forbes summarized the Scottish Church's confession of faith in the form of 55 theses. Karl decided to use these treatises as the basis for holding a religious discussion with noted Swedish theologians in Uppsala. (Hjärne, Harald, Editor. 1903. Svenska akademiens handlingar ifrån år 1886 / Proceedings of the Swedish Academy from the year 1886. Stockholm: The Swedish Academy.)

On November 17, 1608, Forbes appeared alone at the Swedish Academy auditorium before a “packed auditorium” that included leaders of the Lutheran Church of Sweden such as Olof Mårtensson (Latin: Olaus Martini), Archbishop of Uppsala; Laurentius Paulinus Gothus, Bishop of Skara (later bishop of Strängnäs and Archbishop of Uppsala and Primate of Sweden from 1637 to 1646); Johannes Canuti Lenaeus, professor of logic (later Archbishop of Uppsala from 1647 to 1669); Clandins Opsopseus, professor of Hebrew; Johannes Rudbeckius, professor of physics (later bishop at Västerås from 1619 until his death in 1646); Martinas Olai Stenins, professor of astronomy; Samuel Matthiae Malmenius, professor of theology and Greek; Ericus Scepperus, court chaplain; and other noble and high officials of the court who had been ordered to attend. (Ibid.)

Archbishop opened the event with a speech that warned of “false prophets,” clearly referring to Forbes. He then asked Forbes to explain the doctrines that he would use to attack the Church of Sweden. Forbes declared that he had been summoned by the King to present the articles of faith of the Church of Scotland and to defend them in “brotherly conversation.” (Ibid.)

Forbes attempted to read from his theses but was constantly interrupted and challenged by the Lutheran leaders. Even though the debate lasted “until daylight ended,” he was never able to present all the points that the King had wished. According to Church of Sweden historian Johan Baazius the younger (Archbishop of Uppsala from 1677 to 1681), at least twice during the proceedings, Forbes provided no response to points made by the Archbishop and others. As a result, “Baazius took the liberty of writing the familiar words: ‘Ad haec Forbesius nihil,’ which thereby got the appearance of being in the protocol, although they are his own invention.” The phrase “To these things, Forbes said nothing” has since remained a common cliché in Sweden. (Ibid.)

While the Lutheran leaders were not swayed, Forbes’s fifty-five theses were preserved in the Uppsala Library. Forbes left Sweden in 1610, after the King had been forced to abandon his attempts to revise any doctrines of the Church of Sweden.

Forbes then traveled to the Low Countries (the Netherlands) where “he played a prominent part among fellow English and Scottish Nonconformists, most of whom had also left their native country involuntarily.” (de Jong, Chris. 1989. “John Forbes, Scottish Minister and Exile in the Netherlands,” Nederlands archief voor kerkgeschiedenis / Dutch Review of Church History. Leiden: De Gruyter Brill.)

In Middelburg, Zeeland, he served as assistant to Lawrence Potts, who was pastor in the Church of the Company of Merchant Adventurers, a group of powerful and wealthy cloth merchants dating back to the fourteenth century. The Church was formerly a part of the Church of England but had shifted from Episcopacy to Presbyterianism. Forbes succeeded as minister of the church in 1612 when Potts departed the city.

In 1615, Forbes traveled to London to convince King James of his “loyalty and obedience,” in spite of his firm views of Presbyterianism. “He offered his hand-written Certaine Records touching the Estate of the Church of Scotland, in which he explained his views and defended the lawfulness of the General Assembly of July 1605.” (Ibid.)

However, the King demanded that Forbes change his mind on church government and discipline. Forbes refused and his banishment from Scotland was upheld.

After 1619, Forbes occasionally preached at Den Haag (The Hague.) His congregation included the English ambassador, Sir Dudley Carleton, English diplomats, military officers, and James Stuart's daughter, Elizabeth, with her husband, Frederik V, Elector of Palatine.

In 1621, Forbes was one of the founders of the English Synod, formed when the English Church of Delft joined with other English and Scottish churches. Forbes encouraged other churches in the Netherlands to accept the English Synod’s authority over religious doctrine and ordination. At the first meeting of the English Synod on April 20, 1622, Forbes was elected President.

As head of the Church of England, King James learned of the English Synod and “was not satisfied with the way in which it maintained ecclesiastical discipline amongst his subjects in the Low Countries, and he therefore tried to tighten his grip on it.” (Ibid.) He issued strict orders that the Synod follow the orders of the Church of England.

With the support of English Ambassador Carleton, Forbes went to London in 1624 to explain the value of the English Synod and to warn of the objections that would arise over the appointment of an Episcopalian bishop. This time, the King agreed with Forbes. (Ibid.)

However, in 1629, controversy over the English Synod’s approach to ordination was raised with the new King Charles I and William Laud, who became a member of the Privy Council in 1627 and was appointed Bishop of London in the following year. Once more, Forbes traveled to London to appear before the King. Forbes promised that the Synod would “doe nothing cross, or contrary to our Church government here in England.” Once again, Forbes was successful, and the King permitted the Synod to resume its regular meetings. (Ibid.)

However, due to growing political pressure, the English Synod was formally abolished in March 1633. In October 1633, Forbes’s Church of the Merchant Adventurers at Delft was placed under the direct supervision of the Bishop of London. Forbes resigned and died in the Netherlands less than a year later, in August 1634. (Ibid.)

Rev. Forbes had married Christian Barclay, daughter of George Barclay, the Laird of Mather. They had eight children: John, born about 1600, who became a colonel in the Dutch military service and died sometime after 1636 in France without issue (Institute of Scottish Historical Research, University of St. Andrews); Arthur, who also became a colonel in the Dutch military service; Patrick, born about perhaps 1611, who became Bishop of Caithness; James, who became minister of Abercorn; Margaret, who married Andrew Skene, brother of the Laird of Skeen, in Kirktown of Dyce; and three other daughters.

John Forbes of Alford was “held in honour by the reformed churches abroad for his character, talents, and learning, and was revered by many of his own countrymen as one who had suffered for righteousness’ sake” (Stephen, Leslie, and Lee, Sidney, Editors. 1908. Dictionary of National Biography, Volume VII. New York: MacMillan Company.)

Works:

• “The Saint’s Hope, and infallibleness thereof,” Middelburg, 1608.

• Two sermons, Middelburg, 1608.

• “A Treatise tending to the clearing of Justification,” Middelburg, 1616.

• “A Treatise how God’s Spirit may be discerned from Man’s own Spirit,” London, 1617.

• Four sermons on Offending God in Worship on 1 Tim. 6:13-16, 1635.

• A sermon on 2 Tim. ii. 4, Delft, 1642.

• Certain Records touching the Estate of the Kirk in 1605 and 1606, Edinburgh Wodrow Society, 1846.

Comments